Magic Artist Karla Ortiz Among Plaintiffs In Class-Action Suit Against Stability AI

Teysa, Envoy of Ghosts | Illustrated by Karla Ortiz

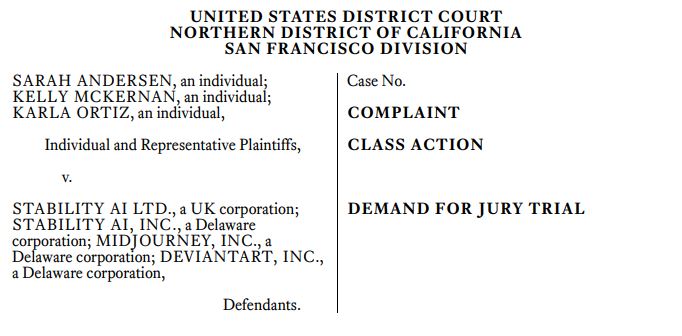

A class-action lawsuit was filed in the San Francisco, California division of the United States District Court last week on behalf of a trio of artists against groups responsible for or using AI art generation tools. The suit, seen here, was filed on Jan. 13.

Named as plaintiffs in the lawsuit are three artists: Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan, and Karla Ortiz. If the last artist sounds familiar, that’s no coincidence. Ortiz is a veteran Magic illustrator, with 18 cards and one emblem to her name, including now-iconic designs like Ashiok, Nightmare Weaver and Teysa, Envoy of Ghosts.

The trio of artists are suing London-based Stability AI, the parent company responsible for AI art generation tool Stable Diffusion, for copyright violations. Also named as defendants are Midjourney and DeviantArt due to their use of Stable Diffusion. The plaintiffs are seeking injunctive relief, an award of statutory and other damages, and certification of their proposed class action.

DeviantArt was named as a defendant due to the website’s release of DreamUp, a paid app built around Stable Diffusion, which has caused the site to be inundated with AI-generated images.

How AI-generated art works, and why it’s a problem

From a user standpoint, AI art is created by simply typing a prompt. Shortly thereafter, art is created by the program, with Stable Diffusion being the most known and popular after debuting in August 2022. On its surface, it seems like an innocent, and frankly revolutionary, tool, allowing anyone to circumvent the years of practice and training needed to create art.

But there’s more to it than that, said Matthew Butterick. Butterick is a member of the legal team spearheading the lawsuit, and on January 13, he published an outline of the plaintiff’s goals. In that summary, Butterick said the suit is “taking…a step toward making AI fair and ethical for everyone.”

In order to create the images based on the prompts provided by the user, generative AI art tools “learn” by training itself on existing images. The problem, said Butterick, is that those existing images — “millions, or possibly billions” of them — are often copyrighted, and used for training without the knowledge and consent of artists.

Butterick said the “value of this misappropriation would be roughly $5 billion.”

Stability AI has publicly claimed that the use of work created by human artists to train its tool meets the standards of fair use, thus absolving the company from seeking consent from or giving credit or compensation to the artists themselves.

Lists of artists whose works have been used to train the AI can be found here (Midjourney) and here (Stable Diffusion). Plenty of names will stand out to both fans of Magic and fans of art in general. Some you’ll remember from art classes, like Picasso, Goya, Matisse, Pollack, or Whistler.

Others are contemporary masters, like Moebius or H.R. Giger, Bernie Wrightson or Frank Frazetta, and others are pop-culture icons, like Shepard Fairey or Banksy.

Still more are the artists that have given Magic its life and look in the 30 years of its existence, like Rebecca Guay, Scott Fischer, Aleksi Briclot, or Magali Villeneuve. And there are dozens others.

Liability and Accountability

Since the game debuted in 1993 through the most recent release in Dominaria Remastered, nearly 1,100 artists have contributed their skills to Magic: the Gathering. That’s 1,100 individuals who’ve poured their talent and expertise into pieces of art that have an immediate and lasting impact on the game itself, and, moreover, the players.

Thousands of artists, including many of those who have worked on Magic, have had their art used for generative AI art training. Some are new, some are veterans, some are classic masters. Some are dead, but most are living, and trying to make a living on creating art.

In a Twitter thread published the day after Butterick’s suit summary, Ortiz called AI media models “deeply exploitative,” with the suit their attempt to hold the creators of those tools accountable. “I am proud to do this with fellow peers, that we’ll give a voice to potentially thousands of affected artists,” wrote Ortiz. “I’m proud that now we fight for our rights not just in the public sphere but in the courts.”

Through the suit, Ortiz said the aim is to encourage the public to scrutinize the “unethical practices” of the companies in question, knowing “we are now starting to scratch the surface of the harm these models could bring, and what we need to do to prevent this harm.”

And it’s not just the artists who are claiming foul play. On January 17, it was reported that Getty Images is also suing Stability AI for using its database of images for training without obtaining the proper licensing. Getty, however, has allowed use of its database in the past for training “in a manner that respects personal and intellectual property rights.” In a statement, Getty claimed that Stability AI “did not seek any such license,” instead ignoring the option and circumventing legal protections “in pursuit of their standalone commercial interests.”

Ultimately, both lawsuits are centered around that commercial impact. Art created by AI tools is derivative of original works and trained on art created by artists who did not give consent to do so. In the suit led by Butterick and the trio of artists, it’s alleged that companies facilitating these tools “skipped the expensive part of complying with copyright and compensating artists, instead helping themselves to millions of copyrighted works for free.” The suit points to many examples of art trained on the output of today’s working artists being generated “in the style of a particular artist and are already sold on the internet, siphoning commissions from the artists themselves.” Further, Ortiz, McKernan and Andersen claim the names of famous artists have been used as marketing tool by the defendants, generating “valuable business from their ability to sell artworks ‘in the style’ that the plaintiffs popularized.”

A Sea Change

In its defense, the legal team representing Stable AI posted a “retort” of Butterick’s summary, calling the suit “frivolous” and likening the advent of AI-generated art to the changes to art brought on by the invention of photography. “The simple facts are, the rights of creators are not unlimited. That’s literally what fair use is,” wrote the team in their retort. “Artists are faced with change in their industry brought on by advancements in technology, and while many embrace it, others fear and resist it, and one can have sympathy for those people. But sympathy does not give them the right to throw fair use in the garbage.”

Today, the technology is not perfect. Images created by generative AI are often the target of ridicule and feature “not quite there” levels of uncanny approximation. Too many teeth, too many fingers. But it’s close, with the diffusion technique that forms the bedrock of the technology being continually improved. And it’s alleged by dozens, if not hundreds, of artists working today that the existence and use of AI-generated art is minimizing their ability to make a living.

The implications of AI art are enormous for not only Magic but any product or piece of media that makes use of commissioned art. “At minimum,” said Butterick, Stable Diffusion’s ability to flood the market with an “essentially unlimited number of infringing images” will inflict permanent damage on the market for art and artists, and further could deprive the world from art yet to be made. McKernan claimed on January 15 that their name has been “used and profited from” a minimum of 12,000 times. “What if I had been paid for every instance? That’s life-changing money for a single mom,” they said. “That isn’t right.”