What Would They Play? Rasputin’s EDH Deck!

Welcome to What Would They Play?

I’m Charlie, I’m a storyteller, creative writer and author; I handle the historical sections of the articles.

And I’m Dan, a Commander player who is obsessed with building thematic decks. I connect the stories to Magic cards to create decks that reflect the vibrant tales of the past.

We take famous or not-so-famous figures from history and make Commander decks based on their lives, philosophies, and histories.

Our articles are meant to be part history lesson, part deckbuilding guide. We believe that decks can be expressions of personal philosophies, so a fun way to learn about historical figures — and flavorful brews — would be to speculate about what sort of Commander deck a given person would play, given their times, opinions, and philosophies.

It’s like a history class, only using the medium of Magic: the Gathering.

This is meant to be an accessible glimpse at the people in question, not a rigorous or definitive biography; we have sources at the end of the article for that!

Let us begin!

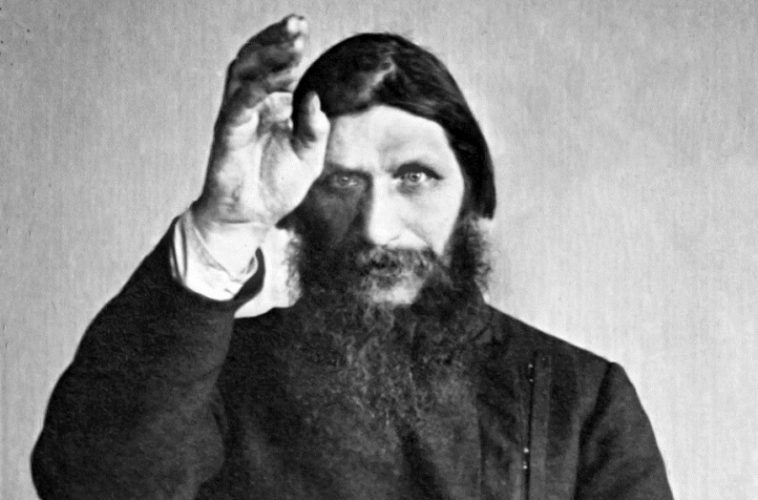

Who was Grigori Yefrimovich Rasputin?

Grigori Yefrimovich Rasputin (usually referred to solely by his last name, but while alive he went by ‘Grishka’ to his friends and intimates–which means “Friend”) was a spiritual advisor, mystic (stranniki), political mover and shaker, and, perhaps most importantly, private and personal healer to the heir to the Romanov dynasty, Alexei, during the final days of the Russian Empire. This Siberian mystic and peasant (and family man, for a given value of the phrase) was a celebrity while alive, a status that only increased with his death (and the rumors surrounding said death) in 1916.

As one podcast put it: “Rasputin was Forrest Gump but hornier.”

Unlike his employers, the Romanovs, who were elevated to the status of saints by the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000 (that sure was…a choice), Rasputin has not been elevated to a sacred position in death formally.1 After the Bolshevik coup in 1917, Rasputin became a symbol of the decadence of imperial Russia; after the end of the cold war, Rasputin was rehabilitated in a nationalist light, an anti-communist figure with shades of antisemitism, just a ‘simple peasant’ whose faith guided the Romanovs in their final days.

Neither of these “pendulum-swings,” as historian Douglas Smith calls them, were accurate depictions of the man (for one thing, whatever his other many sins, Rasputin was not an antisemite).

We’ll be using the mechanic of “deaths”: deep changes in Rasputin’s life and personality that led to the legendary drunken mystic that is known throughout the world. And animated musicals. Death and resurrection is also the theme of Rasputin’s Commander deck, with Orah, Skyclave Hierophant at the helm. Orah, like Rasputin, is a holy man of sorts, and his ability renders his creatures as resilient to death as Rasputin was rumored to have been throughout his life.

This is not, by necessity of length and focus, an exhaustive biography of Rasputin, more like snapshots from his life at key points. There were many Rasputins–as historian Douglas Smith wrote in Rasputin: Faith, Power and the Twilight of the Romanovs: “To separate Rasputin from his mythology, I came to realize, was to completely misunderstand him. There is no Rasputin without stories about Rasputin.”

First Death: Age 28 (1897), Pokrovskoe, Siberia

Grigori Rasputin grew up in the village of Pokrovskoe in Siberia. He was a mischievous child, good with horses, but also afraid of the dark and prone to wetting the bed. He married young–typical for a Siberian peasant of the time–and continued to work the soil. Like his father, Rasputin had a major problem with drinking that would re-occur throughout his life.2

At age twenty-eight–practically middle age for the time period, as Douglas Smith notes–Rasputin had a religious awakening. The sources differ on the nature of the awakening and who was involved; Rasputin claimed in conversations and in his autobiography that St. Simeon of Verkhoturye appeared to him in a dream, saying: “Give all that up and become a new man and I will exalt you.” (The saint, Rasputin claimed, and I am not making this up, cured both his insomnia and bed-wetting which had persisted into adulthood–a fact that his wife must have been pleased about).

Other people, like his daughter Maria Rasputin, claim Holy Mary appeared to her father and directed him to become a holy wanderer.

Whatever the impetus, Rasputin began wandering. This was a sacred occupation in imperial Russia: the blessed wanderers, stranniki, would walk hundred of miles between shrines. With often nothing more than the clothes on their backs, the stranniki were a mix of hobos, mystics, day-laborers, and hedge-prophets who evangelized the oneness of their God and resisted any interference in their life by the state.3

The wandering life of the stranniki can be depicted in Magic through flicker effects, notably Far Traveler, Otherworldly Journey, and Long Road Home. Some of the itinerant Clerics in Rasputin’s deck are Inspiring Overseer, Urbis Protector, and Skemfar Shadowsage, all with powerful enter-the-battlefield abilities that can be retriggered with a blink.

The life of a stranniki was a fundamentally anti-authoritarian, stateless interpretation of Christianity. Rasputin took very well to this life. He typically walked around thirty miles a day through all kinds of weather and terrain (sometimes wearing shackles to mortify his flesh). He did odd jobs, comforted people, begged for food, and preached. Rasputin quit drinking. He controlled his nymphomania through chanting mantras and countless exertions through the countryside, though rumors popped up like mushrooms that sometimes young women vanished into the woods with Rasputin during his wanderings. When men robbed him on the road, he gave them his coat as well as his other belongings, as Christ instructed in the New Testament.

However, unlike other stranniki, Rasputin had a family and children to return to. When he returned home to his wife and children, he would tell them the stories of the wide world he had seen, according to his daughter, Maria. Every time he returned home, more and more people wanted to listen to his stories and hear Rasputin interpret the Bible. They gathered in a cellar that Rasputin himself had dug under his father’s house.

It was the beginning of something new for Rasputin, a germ of power.

Second Death: Age 45, 1914, Pokrovskoe, Siberia

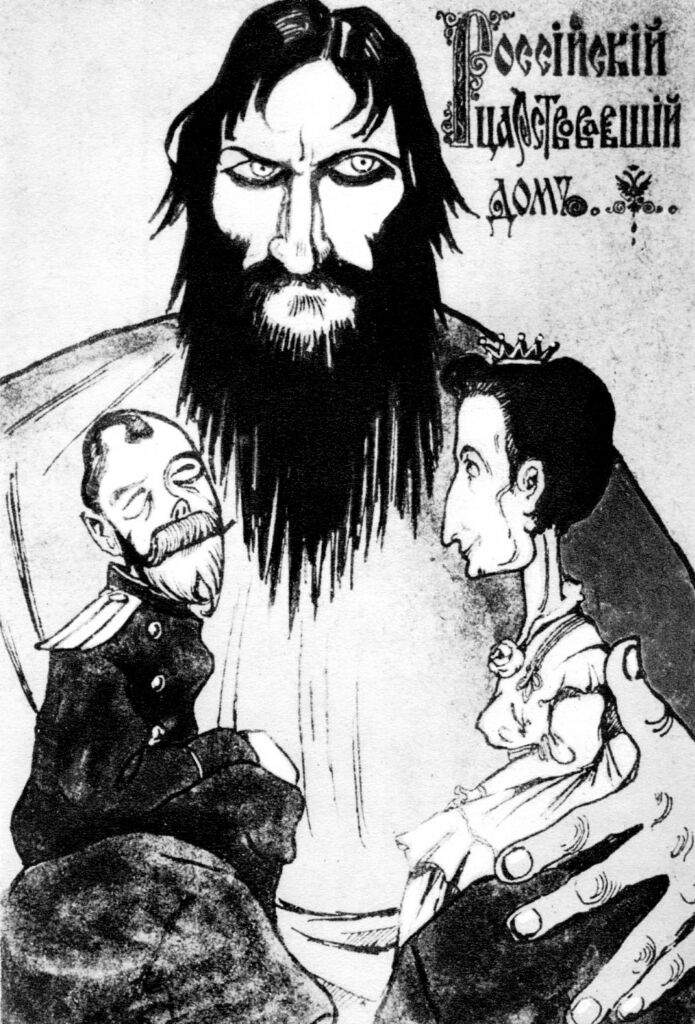

That germ of power expanded rapidly for Rasputin between 1897 and 1914, finally taking him to the top of the Russian Empire as an intimate of the royal family. He had risen rapidly–meteorically–in power in that time. He’d become a confidant of the royal family: Czar Nicholas II, his wife Alexis, and their infirm son, through a mix of schmoozing, mysticism, and undoubted charisma. From his basement ministry he’d traveled ultimately to Moscow, making friends–some of whom just as swiftly became enemies, but, largely, they didn’t matter.

Rasputin’s closeness to the czar’s family made him untouchable, or so he thought. In the words of David Graeber, in Notes on the Politics of Divine Rule:

“Kings will, if they have any possibility of doing so, insist that they stand outside the legal or moral order and that no rules apply to them. Sovereign power is the power to refuse all limits and do what one likes…”

It was this unconditional power–the marriage between the czar (representative and autocrat of the state) and the Orthodox Church–that Rasputin had tapped into by making himself indispensable to the heir to the throne, the hemophiliac child Alexei Nikolaevich.

Just as Rasputin derived power through association with the imperial family, his deck seeks to share the benefits of other players’ advantages. Some of this is through catch-up effects, like Weathered Wayfarer and Keeper of the Accord. Other cards simply reward him as opponents develop their boards, like Archivist of Oghma, Deep Gnome Terramancer, and Authority of the Consuls. Smothering Tithe and Mind’s Eye also help him keep up with players who are drawing tons of cards.

There aren’t many good things one can say about Czar Nicholas II4; at the absolute minimum, he loved his son, which really is a low bar, morally speaking. Where Rasputin’s power came from was the fact that the autocrat couldn’t publicly admit that his heir was anything other than perfectly healthy. The fact that Alexei Nikolaevich was frail, frequently distressed, and only comforted by Rasputin’s prayers or presence could never be admitted to–though Rasputin’s influence over the czar’s wife was also remarked upon, something Rasputin encouraged.

Rasputin’s capacity as a healer appears in his deck as a life-gain theme–a classic pairing with Clerics. In addition to life-gaining Clerics like Traveling Minister (a stranniki in flavor) and Priest of Ancient Lore, there are also plenty of payoffs, like Voice of the Blessed, Righteous Valkyrie, and Valkyrie Harbinger. Vito, Thorn of the Dusk Rose turns his life gain against his opponents–suggesting how his healing powers kept the czar in his thrall.

A key part of Rasputin’s thinking had changed in the time that elapsed: that to be given God’s grace, you not only had to beg forgiveness, but you had to sin. Like, a lot. Really, really sin, enthusiastically and often so you could sincerely repent. Publicly. A sort of divine binge/purge cycle. (The depths of Rasputin’s actual crimes are unclear to this day–given how many Rasputin stories there are, ranging from him being a murderous mastermind to literally Satan–but at best he was a sex pest and at worst he may have been a rapist. We cannot point that out enough, lest the reader think that Rasputin was some sort of anti-hero here).

Now Rasputin was back visiting his hometown in 1914; some minor incident in the Balkans had just happened (the beginnings of World War One, though Rasputin didn’t know that yet), but Rasputin and his family had decided to go on vacation.

It was during this visit (while Rasputin was running after the postman to send a telegram) when he was stopped in the street by veiled and hooded figure in black. It was a woman–later identified as Khionya Guseva, a person inspired by one of Rasputin’s former clerical rivals–who bowed before Rasputin.

Rasputin assumed she was a beggar and reached for his coinpurse, and that’s when Khionya Guseva put the better part of a long knife into his stomach, right by the belly-button. Rasputin ran, screaming that he’d been stabbed; in some accounts, he happened upon a stick and managed to knock his would-be assassin down long enough for an angry mob to lock her up in the town hall and for him to be transported home to relatively safety. Hours later, in the early morning of the next day, the doctors arrived. They did their best with what they had, as Rasputin couldn’t be moved–sewing up the intestines, removing what couldn’t be saved. A priest was sent for to give Rasputin last rites.

Newspapers assumed Rasputin was dead. Headlines declared it in periodicals across the country. Obituaries were written, some mild, others rueful. Turns out, though, that Rasputin was a bit harder to kill than all that, despite the severity of the wound, the unsanitary conditions of the surgery, and everything else working against that outcome.

Rasputin had died and come back to life.5

For now.

Final Death: Age 47, 1916, Moscow.

Rasputin’s final death also wasn’t believed at first.

As Jessie Radcliffe wrote in their paper Rasputin and the Fragmentation of Imperial Russia: “The church, the state[,] and the Russian people developed greater resentment towards the Tsar and fear for the future of Russia because of [Rasputin]. Nicholas and Alexandra chose to protect Rasputin while also trying to maintain their power. It was impossible to do both.”

Russia was by now deep in World War One, and Rasputin’s influence over the royal family had increased as Czar Nicholas went to the front lines to oversee the war personally. Which didn’t help. Millions were dying on the front lines, and those that weren’t were starving. Strikes and bread riots were spreading.

Rasputin had changed since getting a knife in his gut two years previously. He moved with some difficulty. He was in constant pain and it turns out that getting really stabbed will do a number on your libido, so Rasputin redoubled his drinking to cope and serve as a painkiller.

The Romanovs and the aristocracy, however, were in no danger of starving. Nor was Rasputin. He clung to the shield of the czar’s unlimited power like a life-preserver. He desperately needed it. Rasputin was getting threatening letters from all comers; the day before his murder he got a threatening phone call. Prince Yusupov, an arch-conservative and mystic-wannabe, decided that for “patriotic reasons” he and some co-conspirators would kill Rasputin. The original plan was poison–two different kinds–and the pretext of inviting Rasputin to a fun basement party at Yusopov’s place. (It is unclear whether Yusopov ever actually had the poison in the sweetcakes he served Rasputin or put in the port–some accounts maintain that Yusopov was given harmless powder for the job).

Rasputin accepted, arrived late in the evening at the prince’s house, though the poisoned wine had no effect on him beyond drunkenness. Yusopov ran upstairs to his co-conspirators, asking what to do. They decided to shoot him. Yusopov returned downstairs.

Yusopov shot Rasputin in the chest in the basement of his home after entertaining him for some time. Rasputin fell with a grunt. The conspirators made the arrangements to get rid of the body.

Only, according to Yusopov–who wrote all this down in a sensationalist account to sell as many copies as possible after fleeing Russia post-revolution–Rasputin wasn’t dead. He tried to throttle Yusopov (who claims that Rasputin had the ‘green eyes of a viper…staring at me with diabolical hatred…”), before breaking free of the basement and fleeing for the gates, yelling that he was going to tell the czarina all about this. Four more shots rang out from the conspirators and Rasputin fell.

Rasputin was finally dead–ultimately from a bullet to the forehead at close range.

Rasputin’s death might be the most famous thing about him–scores of stories claim that Rasputin was alive when Yusopov and company dumped him in the river (hoping he’d be swept out to sea–but they forgot to weigh the body down with chains and missed one of his boots, which landed on the bank of the river and meant that instead of vanishing without a trace, Rasputin’s body was found a mere three days later).

Rasputin’s Commander deck tries to make his creatures as difficult to kill as the man himself proved to be. It’s packed with spells like Undying Malice, Malakir Rebirth, and Feign Death that turn targeted kill spells into temporary inconveniences. He’s even prepared for board wipes with Cauldron Haze and Cosmic Intervention. With his commander, Orah, Skyclave Hierophant, on the battlefield, he could even end up in a stronger position than before. In case his opponents aren’t helpfully killing his creatures, Rasputin can use Cabal Archon or Pyre of Heroes to get things started himself.

R.I.P. Rasputin!

Much ink has been spilled on the subject of Rasputin. He is perhaps one of the most famous Russians ever to live and is instantly recognizable. His life dramatically illustrated the old Russian anarchist phrase: “Power is poison.”

Vladimir Moss wrote in his paper Who Was Rasputin (2018), pointing out some of the Russian clerics opinion: “Who, in the end, was Rasputin? Bishop Theophan’s opinion was that Rasputin had originally been a sincerely religious man with real gifts, but that he had been corrupted by his contacts with aristocratic society.”

Kerensky–the man who led Russia briefly after the czar abdicated in 1917–is said to have quipped: “Without Rasputin, there could have been no Lenin.” More on that in the coming weeks as we dive into the Russian Revolution.

Grigori Rasputin’s full Commander decklist is below!

- I am compelled to note that a splinter group of the Orthodox Church, The Russian True Orthodox Church, according to historian Douglas Smith, acknowledged Grigori Rasputin as a saint in 1991.

- According to Last Podcast on the Left, one notable incident in this period was as follows: Rasputin was hammered and so decided in the middle of the night that he should steal his neighbors fence via wheelbarrow and sell/use it as firewood. Unsurprisingly, the neighbor took a dim view of this midnight-fence-heist and struck Rasputin a heavy blow on the forehead with a stake–creating a distinct scar on the forehead that ensured Rasputin wore his hair long in part to conceal it.

- Alexei Vasilev, the last head of the tsarist police, wrote that these men and women “represent the out-and-out-Anarchist element among the Russian peasants.” Restless, aimless figures, they avoided all contact with the state chiefly so as to escape any and all social obligations. The stranniki, Vasilev was convinced, needed to be suppressed for the public good. Smith, Rasputin: Faith Power and the Twilight of the Romanovs.

- He brutally put down the first Russian Revolution in 1905, then panicked and ordered the creation of a parliamentary body, the Duma, meant in theory to check his power. He then immediately just made a cubby for the landed classes and cut all other classes out of any national discussion while keeping the right to veto anything they passed that might infringe on his divine right as autocrat. He also supported and funded antisemitic death squads called The Black Hundreds, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

- According to Last Podcast on the Left, Rasputin’s exact words on his would-be assassin, Khionya Guseva, while in recovery were: “That slut with no nose stuck a knife up my ass.” Rasputin didn’t use delicate language.