What Would They Play? Marie-Jeanne Vallet’s EDH Deck

Welcome to What Would They Play?

And I’m Dan, a Commander player who is obsessed with building thematic decks. I connect the stories to Magic cards to create decks that reflect the vibrant tales of the past.

We take famous or not-so-famous figures from history and make Commander decks based on their lives, philosophies, and histories.

Our articles are meant to be part history lesson, part deckbuilding guide. We believe that decks can be expressions of personal philosophies, so a fun way to learn about historical figures — and flavorful brews — would be to speculate about what sort of Commander deck a given person would play, given their times, opinions, and philosophies.

It’s like a history class, only using the medium of Magic: the Gathering.

This is meant to be an accessible glimpse at the people in question, not a rigorous or definitive biography; we have sources at the end of the article for that!

Let us begin!

Marie-Jeanne Vallet and the Beast of Gévaudan (1765)

With WOTC returning to Eldraine, it felt topical to write about beasts and peasants (I’ll spare you my personal squeeing about the ‘peasant’ subtype getting more love in this set), so we decided to write about peasants warding off perhaps one of the most famous beasts of all time: the Beast of Gévaudan, in rural France!

Marie-Jeanne Vallet, of Gévaudan, France, was desperate and brave in 1765. She is identified only as “a young woman” in most sources, making a precise age impossible for the incident in question, but since the shepherds and shepherdesses of Gévaudan region skewed young, it’s probably fair to place her at under thirty.

Marie-Jeanne Vallet doubtless felt mind-bending terror as she crossed a stream and turned to find a large, unknown animal sizing her up, about to pounce.

This was probably the animal that had, in the previous year alone, killed seventeen women and youths through the province and had only just recently stepped up its attacks. The authorities had sent in military forces to kill the beast and to keep order, to no significant effect. The beast continued to kill at will, though some victims survived badly mauled. People feared to tend their herds or move about in open country, the preferred habitat of the beast.

Afterwards, Vallet would describe the beast as looking like an usually large dog in her later sworn testimony.1

Marie-Jeanne Vallet carried a homemade spear. The French peasantry at this time didn’t have much access to guns, as a general rule. The French nobility worried that this would bode badly for them if their subjects were armed; they might take exception to the high taxes or general unfairness of the monarchical system.

She was face-to-face with something that had killed quite a few people, something she doubtless feared herself. She very likely didn’t have time to think as the beast reared up to attack her, but Marie-Jeanne didn’t lose her nerve. According to her testimony, she stabbed the beast in the breast with her spear, stopping its attack. The beast seemed stunned, and toppled into the water, still bleeding.

When she ran to gather witnesses to her deed and returned, the beast was gone.

As this is a story about peasants, it seems only appropriate that Vallet would choose a Peasant as her deck’s commander. Going wide with tokens symbolizes the peasantry’s coming together to face the beast, and Ellyn Harbreeze, Busybody‘s ability works well with all that token creation. With Street Urchin chosen as the Background, Vallet can sacrifice any extra artifacts for damage, just as the peasantry of Gévaudan turned their farm tools into makeshift weapons.

Setting the Scene: The Beast of Gévaudan and Feudalism!

Before we get even further into the peasant struggles, I think it’s important to note that I’ve previously done some work on the subject of the Beast of Gévaudan which I’ll also be drawing from to craft this article. While this article will be discussing the story of Marie-Jeanne Vallet (and other peasants from the Gévaudan region in ancien regime France), it’s more accurately the less-told history from below of the peasants of the Gévaudan region trying to cope with beast attacks in circumstances greatly exacerbated by feudalism. While writing about 20th and 21st century context, nature writer David Quammen writes in his book Monster of God words that apply equally to the French countryside as they do to today’s late capitalist hellscape:

“It’s a general truth if not quite a universal one, relevant from Rudraprayag to Komodo to Tsavo, sometimes noted but seldom quantified or analyzed: predation is costly and the costs are unevenly distributed. Large predators cause more material loss, inconvenience, terror, suffering and death among poor people (specifically poor people who live in rural circumstances within or adjacent to the habitat) and among native peoples adhering to traditional lifestyles on the landscape (who may only be ‘poor’ in the sense that they aren’t insulated by material wealth and have little political power) than to anyone else. Proximity plus vulnerability equals jeopardy.” [Emphasis mine]

France has had a long and complicated history with oppression, nobility, and wolves.2

To summarize: the French peasantry in general and in Gévaudan in the late 1760s in particular were uniquely vulnerable to the predatory attention of beasts due to the feudal structure of their society, over-taxing from centers of power both local and national, the difficult terrain of the province (thin topsoil, frequent rains and mist in the uneven, volcanic terrain), and dependence on livestock for subsistence, food, and more in hard times.

Children as young as five or six were sent to shepherd sheep or cows in the meadows, putting them at enhanced risk for wolf-predation, their small size and isolation making them easy prey.

Smith, in Monsters of the Gévaudan, notes that it was common practice in Gévaudan winters to shelter the animals in the same house as the farm families for an extra source of heat. Most of the peasants in this region were just above subsistence level farming, when royal taxes were accounted for, so the peasants didn’t have much to work with to defend themselves from the beast; just makeshift weapons and repurposed farm implements. In Vallet’s EDH deck, she repurposes artifacts to deal damage with the Street Urchin Background. Cheap artifacts that replace themselves, like Chromatic Star, Experimental Synthesizer, and Ichor Wellspring, are great for this. Prized Statue, Nimblewright Schematic, and Servo Schematic produce additional artifacts to sacrifice and boost up Ellyn’s ability. Pia and Kiran Nalaar and Orcish Vandal give additional options for sacrificing those artifacts.

To make things worse, France had very recently just lost the Seven Years War (a certain hippopotamus-toothed slave-owning Virginian in Western Pennsylvania we are all familiar with started that global kerfluffle) and was reeling financially–thus driving up taxes–and from a collectively bruised ego. Strict censorship laws would not allow criticism of the king or government.

So the French press (no, not that kind) was desperate for something, anything, to change to the topic from disastrous global military defeat.

In 1764, in Gévaudan, mysterious animal attacks began.

Send in the Army: Duhamel’s Bizarre Adventure!

Nor was Marie-Jeanne Vallet the only resident of Gévaudan to resist the beast desperately and succeed in driving it off. It seemed that the natives of the province had far more success in putting the beast to flight than the military or hunters brought in from outside the province. More success, at any rate than Duhamel, the local military commander with 30,000 men sent to contain the crisis by the authorities.

Duhamel and his dragoons were military men, not hunters, and certainly unfamiliar with the difficult landscape and people of Gévaudan. Macho-types. He didn’t get on terribly well with the shepherds and farmers of Gévaudan, already a prickly bunch at the best of times with a long-standing distrust of outsiders. Worse, he would take men away from their farming/herding duties to join his ‘beast hunts’, which in a hardscrabble place like Gévaudan could have catastrophic effects on households winter food supply. Military troops were mocked by the hardscrabble residents of Gévaudan. Duhamel’s shows of force and wide sweeps through the countryside turned up nothing but a few dead wolves.

After a few failed hunts, Duhamel decided to dress his men in women’s clothing in an attempt to lure the beast into attacking them, since he noted the beast tended to ambush women (quite unlike Magic‘s Beloved Princess, who big monsters can’t seem to find at all). It didn’t work. Worse, according to Smith’s The Monsters of Gévaudan, many of the soldiers deserted (still in drag) and took up the noble art of highwaymanning, leading to a crime wave in the rural township that didn’t endear Duhamel to the peasantry of Gévaudan any as his men plundered what few reserves the people had or made nuisances of themselves.

Even when he was doing his job, Duhamel was disliked. During several of his battues–wide encircling movements meant to flush the beast from cover to be shot–the conscripted men of Gévaudan left their posts to go to the local tavern and make fun of the outsider. Classic.

Still, Duhamel sighted the beast several times and recorded in his notes: “The beast’s father was a lion, God knows what it’s mother was.” Unnervingly, what shots struck the beast throughout its life seemed to be ineffective. This says about as much about the firearms of the day as it does the beast’s supposed invulnerability. Channeling the apparent indestructibility of the beast, this deck has several ways to make creatures indestructible. Basri Ket and Grand Crescendo do so while also being token producers for Ellyn’s ability. Akroma’s Will and Flawless Maneuver take advantage of the fact that Street Urchin is less likely to be removed from the battlefield. Mondrak, Glory Dominus can become just as indestructible as the beast and supercharges the token strategy.

There was a reason for this seemingly disproportionate response to a series of rural beast attacks. France had just been truly trounced in the Seven Years War as mentioned above3 and overall, morale was low.

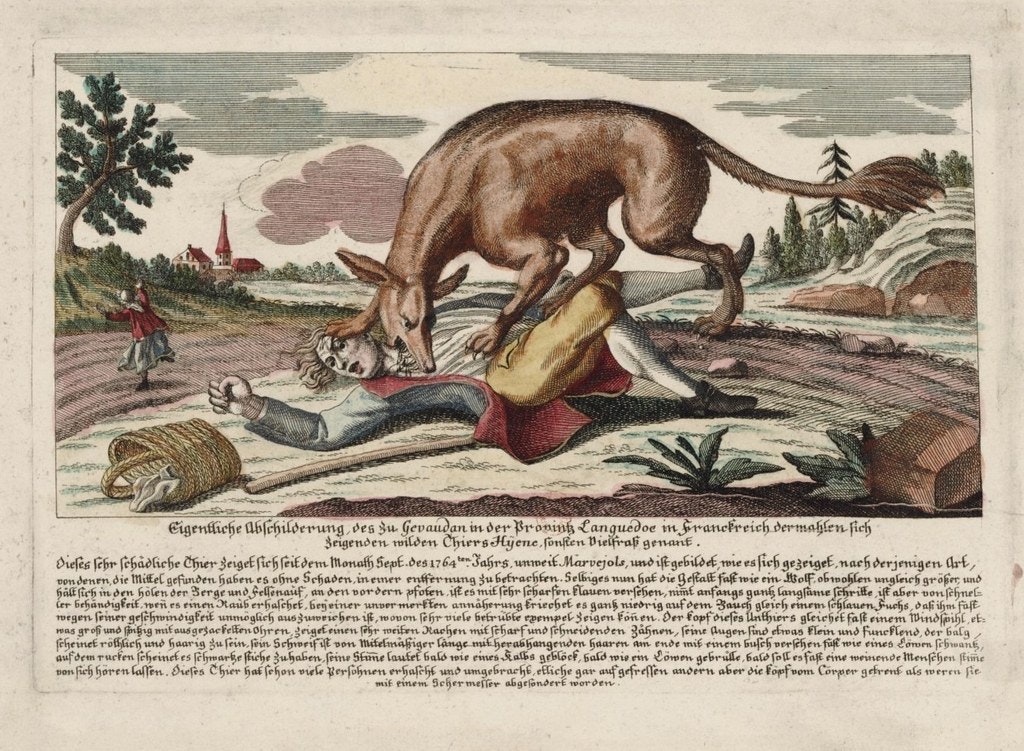

That, and as Taake observes from Smith, this was the beginning of the press as a formalized institution. This story couldn’t be passed up. It was a tale guaranteed to sell: young women being killed, a mysterious animal; it was dynamite stuff and presented a peak opportunity to regain national honor. Accounts of the beast reached far into Europe and even the New World; it could be said to have gone viral. In German editions, the beast looks as if someone has forced a kangaroo onto four legs and given it a killer set of fangs.

Certainly the aristocracy had their reasons for wanting the beast dead. Political legitimacy, for one thing, was less a matter of pest control, and now a question of demonstrating their power over this creature’s rising reputation into legendary status.

That, and according to Taake, the French government simply couldn’t give up upon the notion that the beast was a wolf. Twice the government envoys tried to declare victory by shooting the largest wolves they could find, stuffing them4 and proclaiming to all and sundry that the dread reign of terror was over–only for the attacks to continue.

If the beast had been a wolf, the people of Gévaudan would have said as much. And the attacks continued.

Jeanne Varlet and Jacques Porterfaix fight the Beast!

It seemed that only the local victims of the beast had any track record of making the creature flee and only after determined opposition. The monarch was proving so ineffective one would think there was a Spirit of the Labyrinth on the battlefield.

This was a local problem, no matter what Versailles said, and the locals repeatedly showed themselves capable of driving off things that might have been the beast. They grew increasingly resentful of outside high-handedness and misbehavior. For example:

Jeanne Varlet–also written as Chastang–and her children were eating breakfast in the garden, in Taake’s recounting of their attack, in March 1765. The beast jumped over their garden wall and grabbed one of her children by the head. Jeanne tried to wrest her son from the beast’s jaws. As a battle between the beast and the frail mother, there could be only one outcome, no matter how she beat it with a rock, climbed onto its back, or hit it in the genitals. The beast jumped over the garden wall with the boy clasped in its jaws, but was driven off by Jeanne’s son returning home with a pike and herding dog, surrendering its prize and vanishing into the woods. Jeanne was wounded by the beast’s claws, and despite her efforts her youngest son died of his wounds inflicted by the beast. The king of France sent her 300 livres in recognition for her bravery.

Jacques Portefaix and six other twelve-year old children armed with crude pikes sustained several severe wounds fending off the beast later that same year on a cold winter’s day. Portefaix was rewarded with 300 livres for his his bravery, according to Taake, and the same amount was given to his companions (compare this to the typical bounty for wolves at the time, a measly 6 livres).

This is where the production of creature tokens comes in for the deck. The people of Gévaudan could only rely on each other, so having a large number of creature tokens was the best way to stay safe. Rabble Rousing particularly evokes the flavor of Citizens banding together against the threat. Bennie Bracks, Zoologist and Rosie Cotton of South Lane add extra benefits to all that token creation, and Anointed Procession takes it to another level. And, of course, all of that feeds into Ellyn Harbreeze’s card filtering ability.

Fighting the beast wasn’t impossible, but killing it seemed to be. Certainly, the military sent in by the French government hurt more than it helped. Speaking of:

D’Eneval, royal wolf-hunter, was the next sent by the King to solve the crisis. He brought a better understanding of the hunt and proper tactics. He understood that Gévaudan was a nightmare for hunting–there were swamps that made horses useless as transport, the mountains of the region have volcanic origins that make them impermeable to water, and sudden mists could and did interfere at any time. Combined with the hostility of the locals, D’Eneval had a difficult task ahead. So he didn’t even attempt it and left the hunting to his son, much to the disgust of the populace.

He was relieved by Francoise Antoine, the king’s arquebus bearer, to go and sort this beast out. This he failed to do. What he did do was allow a large wolf with a crooked paw to be killed and claimed it as the self-same beast. Embarrassingly, the actual beast didn’t get the memo and only increased its killing spree. Three weeks later, Antoine shot a larger-than-average wolf and declared this one was the beast, pinky-swear for real this time. Everyone’s stories suddenly changed–the beast had always been a wolf.

Eyewitnesses swore upon seeing this animal that it was the one who had menaced them. Antoine returned to Paris, collected his pension, and his own son did a traveling tour of France with the taxidermied body of the “Beast of Gévaudan”. Officially, the matter was settled. The Crown’s supremacy had been asserted over nature, now the papers could move on to more important things.

Except That it Wasn’t Over (1767)

Marie-Jeanne Vallet–like countless others of the Gévaudan peasantry–is memorialized for her courage, but Jean Chastel, another local (though much more unpleasant a character) ultimately gets the credit for the final kill of the beast.

Jean Chastel, an innkeeper, had a production manager’s sense of opportunism and timing; more’s the pity. His first appearance in the saga has him telling Francoise Antoine’s horsemen that they can ride through a certain swamp with no trouble whatsoever, which turned out to be wildly not true, and he knew it. Gives you a sense of his character. He was even suspected of being a werewolf in his own time.

His brief imprisonment due to quarreling with Francoise Antoine’s dragoons coincided with a brief pause in beast attacks, leading people to believe that he was either training the beast or was connected to it in some way.

In 1767 he shot a wolf and claimed it as the legendary beast. It is from Chastel’s account that we see the first written mention of a silver bullet being fatal to werewolves. Chastel was by all accounts a thorny and persnickety person, a hard man to like let alone admire. He tried to haul “his beast” to Paris in a cart, only for Louis XV to demand the stinking thing be buried in the garden at Versailles.

The official, line was clear: Francoise Antoine had killed the beast, and shut up about it already. This Chastel did not do.

Whoops.

But two months later in 1767, the attacks resumed, in what Taake calls “the year of killed children”. The end of the beast of Gévaudan came two years, not from a hunter’s shot, but from the widespread use of poisoned bait, according to Taake’s accounts. The beast–whatever it was–likely died in the foothills of Gévaudan, alone. But it is a neater narrative to claim that the peasants triumphed ultimately due to their own pluck and grit. Certainly, this incident is illustrative of the tension between agrarian peasants and the upper classes in French society.

So, how do we slay the beast in the deck? For our removal suite, we’re mostly looking at effects that destroy large creatures. Sweepers like Retribution of the Meek and Elspeth, Sun’s Champion are likely to be one-sided or nearly so, since this deck has very few creatures with power 4 or greater. The Battle of Bywater has the added bonus of making a bunch of Food tokens to fuel both Ellyn’s and Street Urchin‘s abilities. In case of monsters with pesky indestructibility, The Wanderer can exile them and Meekstone can lock them down.

Marie-Jeanne Vallet has tons of iron bent into an image of herself giving an attacking beast what for. She even survives in a strange way as a bit character in an American television program.5

Lessons in History from Gévaudan

Official, Versailles-sponsored history claimed that Francois Antoine had killed the beast, local Gévaudan tradition held that Jean Chastel had fired the terminal shot. How the animal actually died doesn’t really seem to matter, it’s a legend now–but the narrative of peasants doing their best for themselves in the face of outside interference is one that is valuable to keep in mind today.

For the Crown, the beast was a political headache at worst; for the people who lived under the yoke of feudalism in Gévaudan, the beast a symptom of larger exploitation and the difficulty of daily life. The situation of the Gévaudan peasants–poor, overtaxed, precarious–was not at all unusual in feudal France. Indeed, it would become even more common as the century wore on. Anarchist and historian Peter Kropotkin writes in his history of the period just after the Gévaudan attacks:

“The accession of Louis XVI to the throne in 1774 was the signal for a whole series of hunger riots. These lasted up to 1783; then came a period of comparative quiet. But after 1786, and still more after 1788, the peasant insurrections broke out again with renewed vigor. Famine had been the chief source of the earlier disturbances, and the lack of bread always remained one of the principal causes of the risings. But it was chiefly disinclination on the part of the peasants to pay the feudal taxes that spurred them to revolt.”

In the two histories of the same events in Gévaudan, one can see the tensions that would eventually boil over into a social revolution before the end of the century.

Marie-Jeanne Vallet’s full EDH deck is below!

Sources:

- Smith, Monsters of the Gévaudan

- Taake, The Tragedy of a Deported Beast

- Kropotkin, The Great French Revolution 1789-1793

- There has been a great deal of speculation as to the identity of the Beast of Gévaudan. Guesses include: a wolf, a wolf-dog hybrid, a werewolf, a hyena, and a sub-adult male lion escaped en route to a menagerie. I agree with the Taake’s 2019 National Geographic sponsored opinion: the beast was a sub-adult lion. While wolves may have picked off a child or ten during these years, nothing else fits the pattern of attacks, the preference for open country over forest, the sheer size of the beast, and other details presented in eyewitness accounts. This is also simplifying a fair amount: some people have put forth the idea of multiple beasts and the even simpler explanation of collective hysteria. It is certainly in the realm of possibility that Gévaudan was having three bad wolf years and this simply compounded into the creation of a beast myth.

- To get a fuller sense of how pervasive wolf predation on French peasants was in the feudal era, I heartily recommend this paper:

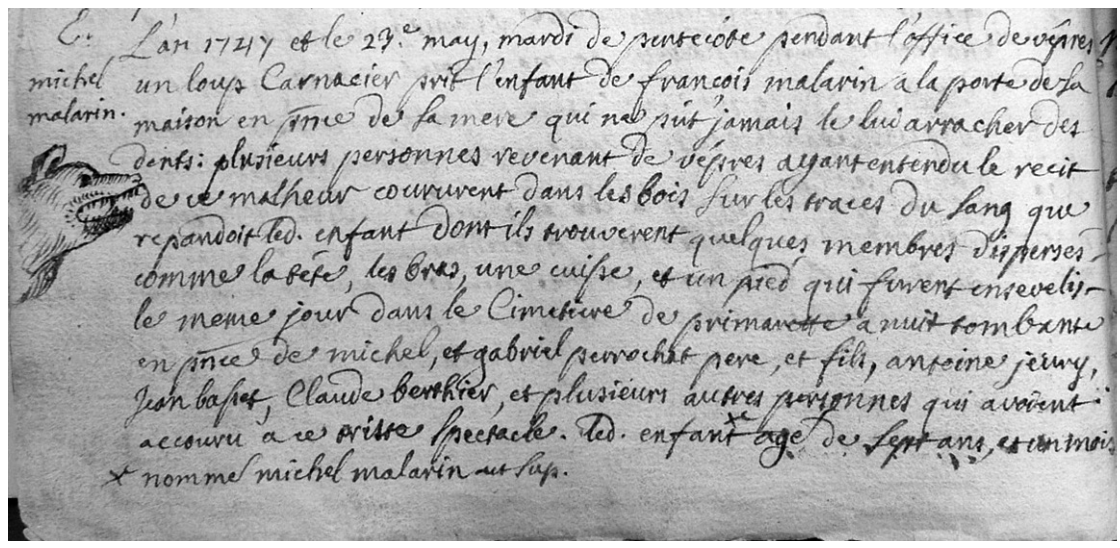

The Story of a Man-eating Beast in Dauphiné, France (1746-1756) This was one of the more formative articles in shaping how I approached this. The paper covers a period immediately before the beast attacks in Gévaudan, but hits many of the same notes. While other authors listed here (Taake, Quammen, Smith) all mention that France had a chronic problem with wolves, this was the paper that truly brought home to me how deeply rooted the problem was.

- This is the trouble with being Louis XV. One fights a long war with the British and Prussians and at the end of seven years end up with nothing. That will bruise your ego, and make you eager to take any public-relations victory you can get. Louis was something of a hands-off ruler. According to Duffort de Cheverny, “He was the most excellent of men but, in defiance of himself, he spoke about the affairs of state as if someone else was governing.”

- In the case of the Wolf of Chasez, sometimes adding human limbs into the animal’s gut to make the claim it was the beast more convincing, as Taake claims. This just proves that wag-the-dog–or wolf, as the case may be–approaches to serious problems are older than we give them credit for.

- Teen Wolf, in case you were wondering. Jean Chastel is there too.