What Would They Play? Albert Camus's Rebel EDH Deck

Welcome to What Would They Play?

I'm Charlie. I'm a storyteller, creative writer, and author; I handle the historical sections of the articles.

And I'm Dan, a Commander player obsessed with building thematic decks. I connect the stories to Magic cards to create decks that reflect the vibrant tales of the past.

We take famous or not-so-famous figures from history and make Commander decks based on their lives, philosophies, and histories.

Our articles are meant to be part history lesson, part deckbuilding guide. We believe that decks can be expressions of personal philosophies, so a fun way to learn about historical figures -- and flavorful brews -- would be to speculate about what sort of Commander deck a given person would play, given their times, opinions, and philosophies.

It's like a history class, only using the medium of Magic: the Gathering.

This is meant to be an accessible glimpse at the people in question, not a rigorous or definitive biography; we have sources at the end of the article for that!

Now let's go on to talk about Albert "At Least I'm Not Sartre" Camus!1

Existentialist Rebellion: "The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion."

Existentialism is the belief that life has no inherent meaning and so each person must create their own. Unsurprisingly, the premise of existentialism can lead to nihilism, the belief that absolutely nothing matters. It's not a long jump from nihilism to complete despair and from there, acceptance of things as unchangeable.

In his essay The Myth of Sisyphus (1942), Camus pits the human desire for meaning against the uncaring nature of the universe. These opposing forces are reflected in his choice of commanders for his deck: Trynn, Champion of Freedom

Camus found absurdity in this contrast, and both sides are presented in his deck. The fickle, unreasonable world is presented through a suite of removal inflected with a touch of randomness, including Wild Magic Surge

The world was increasingly unfree when Camus published The Rebel. In 1951--as today--there were plenty of reasons for concern. It was the very beginning of the Cold War; both the United States and USSR had nukes and could end the world in a blink.

The Second World War crushed the hopes of anarchists and leftists the world over for widespread social revolution in the wake of fascism's military defeat. Sartre, and much of the academic left, was inclined to favor supporting Stalinism against capitalism, pleading the classic argument of 'lesser evil'.

Camus advocated an anarchist position in The Rebel, against centralized authority and alliances of convenience with authoritarians. This marked the beginning of the end of his relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre.

In The Rebel, Camus rejected nihilism as a salve or a way to live. Rebellion against the absurd nature of life that could end at any moment, not despair, is the tonic he recommended.

And he used the word rebellion (not revolution) very deliberately.

Camus With the Anarcho-Syndicalists

To understand how Albert "Spain In Our Hearts"2 Camus reached and honed this distinction between rebellion and revolution, we'll need to hopscotch a bit backwards through time, before the war.

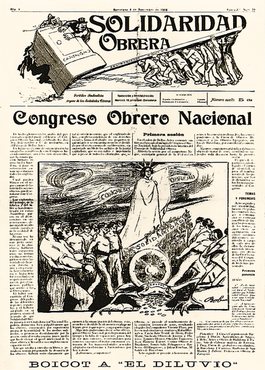

When the Second World War broke out, Camus moved to France and joined the French resistance, writing for the underground newspaper Combat with his then-friend, Jean-Paul Sartre. Camus became closely associated with the anarcho-syndicalist CNT-FAI, who were in exile from Spain and headquartered in France. Albert Camus found solidarity with the CNT-FAI and even wrote for their newspaper, Solidaridad Obrera.

Historian Nick Heath notes: "[Camus] was always there to support at the most difficult moments of the anarchist movement, even if he felt he could not totally commit himself to that movement."3

Camus was anarchist-adjacent despite his many other flaws. Such flaws included but were not limited to repeatedly cheating on his wife (to the point that in 1954 she attempted suicide) or ultimately being unable to condemn French imperialism in Algiers.4

Albert Camus was particularly vociferous in his protests against the death penalty, as one might notice from his works like Reflections on the Guillotine (1957), The Rebel (1951) and Neither Victims Nor Executioners (1946).

Neither Victims Nor Executioners was written after the end of major hostilities of the Second World War. It foreshadows a lot of the points the Camus would make in his later career, particularly in The Rebel. A major through-line on this was his opposition to central authority and the act of Murder

"But I have always held that, if he who bases his hopes on human nature is a fool, he who gives up in the face of circumstances is a coward. And henceforth, the only honorable course will be to stake everything on a formidable Gamble

: that words are more powerful than munitions."

Camus became deeply involved in agitating for amnesty for anarchist prisoners, particularly in the case of the Spanish anarchists. For example in 1952, French intellectuals organized against the execution of Spanish anarchists, the majority of them picked up in the fascist repression against anarchists in 1949-1950 in Franco's fascist Spain. Both Camus and Sartre spoke, publicly condemning the planned executions of anarchists and union members in February 1952 by the Franco regime. A month later, four of the prisoners were pardoned, and the remaining five executed.5

Where Camus in real life protested against executions, his deck allows him to intervene more directly when his creatures are threatened. Spells like Malakir Rebirth

It was through this period of closeness with the anarcho-syndicalists that Camus wrote one of his most famous works, The Rebel (1951), which acts as an extension and elaboration of the principles stated against such arbitrary demonstrations of power like the death penalty.

Rebellion vs. Revolution

Camus's concept of rebellion that he explores in The Rebel picks up where egoist anarchist Max "The Forehead" Stirner left off a century prior.6 Camus writes on the distinction between rebellion and revolution, using the French Revolution as a guide:

"That is why rebellion kills men while revolution destroys both men and principles. But, for the same reasons, it can be said that there has not yet been a revolution in the course of history. There could be only one, and that would be the definitive revolution. The movement seems to complete the circle already begins to describe another at the precise moment when the new government is formed.

The anarchists, with Varlet as their leader, were made well aware of the fact that government and revolution are incompatible in the direct sense.

'It implies a contradiction,' says Proudhon 'that a government could ever be revolutionary, for the very simple reason that it is the government."

The revolutions of the 20th century were all ultimately coopted by authoritarians who increased the power of the centralized state, despite notable anarchist resistance. In Camus's view, this was not an accident or bad luck, but inherent in the nature of a revolution that bases itself on gaining and then monopolizing political and military power.

Naturally, this opinion did not win him any friends among the authoritarian communists and their sympathizers, including Sartre.

This difference of opinion caused a significant split between Sartre and Camus. Sartre advocated allying with the Stalinist USSR, arguing that it could become more democratic and it contained a large part of the world's working class. Camus rejected his old friend's analysis. In Camus's opinion, one couldn't argue towards reforming systems of domination--capitalist or state capitalist--only rebel against them.

Rebellion, in contrast to a revolution, doesn't concern itself with political power or using the machinery of the state to attempt to patch holes or pass reforms. A rebellion denies the authority of the state, denies hierarchy, and seeks to allow people to organize themselves in solidarity.

When it comes to rebellion, there are few who do it better than Rebels. The majority of Magic's Rebel creatures are also Humans, tying in well with the theme suggested by Camus's choice of commanders. Lin Sivvi, Defiant Hero

Rebellion As Solidarity: "I Rebel, Therefore We Exist."

Rebellion is the ultimate demonstration of solidarity. In Camus' definition, it stands in stark contrast to revolutionary 'discipline', and cuts across all possible barriers--geographic, generational, linguistic, cultural--the act of individual rebellion as the basis for solidarity.

Better, Camus argues that rebellion encourages people to act on their own initiative and empathy rather than to await orders from on high. In those moments of rebellion, he writes, a person is "not simply a slave opposing his master, but a man opposing the world of master and slave."

Camus points out that these spontaneous displays of defiance and empathy, rather than being 'undisciplined,' are the mortar for any social or radical movement. It is because they transcend all those otherwise formidable barriers of class, language, and culture (in the modern day, thanks to social media, even geography is easily conquered) by one act of rebellion. For a modern example, de-arresting someone in the middle of a protest is an act of rebellion and solidarity, for example, as well as just good practice.

The concept of solidarity is exemplified in Cathars' Crusade, where every new member of the movement strengthens all who came before. Anthem effects, like General Kudro of Drannith and Rally the Ranks, unite all your Humans regardless of color (of mana) or class (e.g., Wizard, Soldier, etc.), and any such hierarchies can be washed away entirely by Mirror Entity (which, don't forget, is a Rebel--potentially serving as a tutorable finisher in the late game).

That's All!

Check out Albert Camus's full Trynn and Silvar deck below. The list is rounded out with some death triggers to synergize with Silvar sacrifice ability and keep cards flowing.

Albert Camus and the Question of Sacrifice

View on ArchidektCommander (2)

Lands (38)

Creatures (39)

- 1 Amrou Scout

- 1 Beskir Shieldmate

- 1 Big Game Hunter

- 1 Blightspeaker

- 1 Chaos Defiler

- 1 Cho-Manno, Revolutionary

- 1 Cruel Celebrant

- 1 Dauthi Voidwalker

- 1 Defiant Falcon

- 1 Defiant Vanguard

- 1 Dutiful Attendant

- 1 Garna, Bloodfist of Keld

- 1 General Kudro of Drannith

- 1 General's Enforcer

- 1 Gerrard, Weatherlight Hero

- 1 Grim Haruspex

- 1 Hero of Bladehold

- 1 Immersturm Predator

- 1 Jerren, Corrupted Bishop // Ormendahl, the Corrupter

- 1 Jirina Kudro

- 1 Judith, the Scourge Diva

- 1 Liesa, Forgotten Archangel

- 1 Lin Sivvi, Defiant Hero

- 1 Mirror Entity

- 1 Neyali, Suns' Vanguard

- 1 Novice Occultist

- 1 Rakdos, the Showstopper

- 1 Ramosian Captain

- 1 Ramosian Commander

- 1 Ramosian Lieutenant

- 1 Ramosian Revivalist

- 1 Ramosian Sergeant

- 1 Ramosian Sky Marshal

- 1 Resistance Skywarden

- 1 Species Specialist

- 1 Spiteful Prankster

- 1 Sungold Sentinel

- 1 Vengeful Strangler // Strangling Grasp

- 1 Zulaport Cutthroat

Enchantments (8)

Instants (8)

Artifacts (3)

Planeswalkers (1)

Sorceries (1)

- The header quotes are all taken from The Rebel unless otherwise noted

- The full quote, referring to the Spanish Civil War, reads:"Men of my generation have had Spain in our hearts. It was there that they learned ... that one can be right and yet be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit, and that there are times when courage is not rewarded."

- For more on Camus's relationship with anarchists and anarchism in general, I recommend Nick Heath's treatment of the subject as well as Peter Marshall's discussion of Camus in his book Demanding the Impossible.

- Peter Marshall captures Albert Camus near the end of his life in this quotation from Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism:

"... he [Camus] remained faithful to his roots, a left-wing colonialist, an outsider on the African shore and in metropolitan France, a man who was prepared to accept injustice for a place to live in the sun with his kind."

Other authors have dealt with the issue of Camus and Algiers in greater detail here and here. The last, a piece by Oliver Gloag, goes in depth to examine Camus's relationship to Algierian liberation and the French empire. - It is interesting to note that two of the executed anarchists (Pedro Adrover Font [nicknamed 'El Yayo'--'grandfather'] and Santiago Amir Gruanas [nicknamed 'El Sheriff']) had been close with and worked with Quico Sabaté in Barcelona resisting the fascists after the Second World War.

Source: [A Leaflet [protesting the execution of members of the Tallion group]" (1952)] I'm also obliged to note that Camus died in the same year as Quico Sabate (1960). - Stirner advocated 'insurrection' in The Ego and Its Own rather than revolution, which was simply a changing of hats: 'The [French] Revolution aimed at new arrangements; insurrection leads us no longer let ourself be arranged...'