Flavor of the Month: Magic’s Wordiest Cards

“Prometheus, thief of light, giver of light, bound by the gods, must have been a book.”

Welcome to Flavor of the Month, where we build decks flavor first!

Last month… well, someone got a hold of this column and took over with a deck that used all either textless spells or Counterspell/Humility effects that made it so you didn’t have to read your opponents’ cards. He also said some things about my combined love of literature and Magic‘s flavor that, frankly, I took a little personally! (It might have been because he called me out by name several times that it felt so personal.)

So this time, let’s get back on the right track. Given the lack of linguistic flavor last month, we need to do more than just go back to the status quo; we need to up the ante. Let’s build a deck you actually need to sit with, read, and ruminate on! Let’s play with some wordy cards!

Granted, finding wordy cards won’t be hard: all you have to do is head to your LGS and crack a recent booster pack.

If you’ve been feeling like Magic: The Gathering card designs are getting more and more complex in recent years, you’re not alone. When was the last time you saw a vanilla creature (a creature with no rules text) in a new set, or even a French vanilla one (no rules text except keywords, like flying)? Cards have more words than ever, and ever since Zendikar Rising a bunch of them have even more words on the back half of the card. Modal double-faced cards (MDFCs) make for interesting designs, but they’re also a good excuse to fit more abilities on a single piece of cardboard. Since 2020, by my count around half of the mainline Standard-legal sets utilize some form of double-sided mechanic.

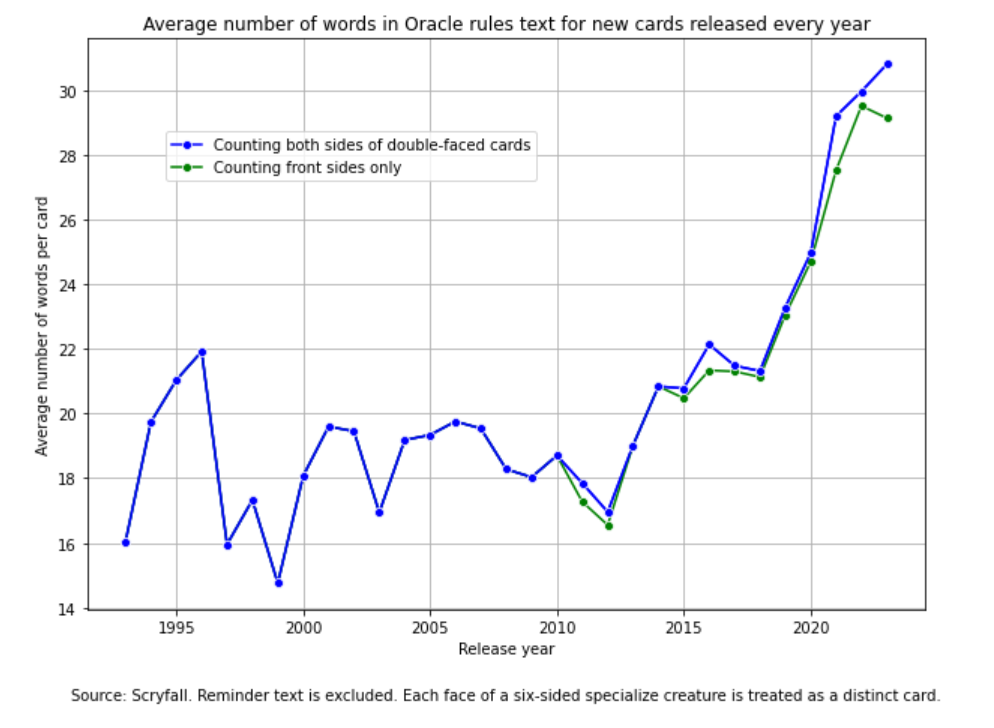

The data bears this trend out, as well. The following chart comes courtesy of Frank Karsten’s MTG wrapup at the end of last year:

Yep. Average word counts have skyrocketed since 2019, and while an extra nine or so words doesn’t seem like a lot, when you consider that you’re reading that much more every time, the cognitive load gets heavy. This is even before considering that new keywording has reduced the number of words on a card without changing the many things it does; for example, “Look at the top card of your library. You may put it into your graveyard” now reads “surveil 1.” Same effect, fewer words; the rules text on Consider went from 19 to 5. And even with the additional keywording shrinking text, the average is increasing!

If you were wondering, the wordiest Magic card based on Oracle text is Camouflage, at 98 words–longer than some short stories, if you’re reading flash fiction. One word less, at 97, is Illusionary Mask, then the third-wordiest card is Word of Command at a relatively tamer 86 words. (Thanks to Alex Lapp of Commander Spellbook and The Social Contract podcast for those numbers!)

As these three examples show, many super-wordy cards are casualties of being printed at a time before Wizards of the Coast started getting more careful with their card wordings. Magic is an incredibly complex game (try to print out the entire comprehensive rules and see how many pages it takes! Actually, for environmental reasons, don’t do that); vague or inexact rules texts on cards cause problems if there isn’t a clear way to handle a unique effect. Many older cards have received Oracle updates over the years to make them function within the new standard of MTG rules. In some cases, like those three cards, making them work as intended requires a lot of very precise language. Word of Command essentially functions as “Make your opponent cast something of your choice from their hand.” But to function in Magic‘s rules, those 11 words don’t cut it.

As Frank’s chart above shows, cards are just getting much wordier recently, so we can’t blame the last eight years on Oracle updates. Today, we’re going to lean into the convoluted and messy, both text- and mechanic-wise. Let’s get wordy, long-winded, loquacious, and verbose. Let’s confound, stupefy, and hinder. Let’s get lost in the semantics (which are just game rules when it comes to language).

Let’s build a deck to get lost in. And if we want to frame our of deck in an appropriate stylistic shell, what better way than to fashion it after a wordy, complicated masterpiece–Mark Z. Danielewski’s novel House of Leaves?

Ingredients

House of Leaves was released in 2000, and despite it being a fairly experimental literary horror/suspense book, it became an international bestseller. Usually, the more avant-garde books out there fail to break into the mainstream; this thing has “cult classic” energy for sure. But luckily for those of us who wouldn’t have found it if it was only literary hipsters passing it around, the quality of the concept, the story, and the writing brought it plenty of acclaim and popularity.

There are a few things that make House of Leaves complex. First off, the framing of the story. Or, really, I should say stories plural, since the book is a nesting doll of tales. At the center of the book is a house that is larger on the inside than it is on the outside. A hallway one day just appears in an otherwise blank wall, and it leads to a labyrinth that is pitch black, cold, and shifts its configuration without warning. Through multiple explorations, all recorded via video camera, the owner, Will Navidson, discovers the “house” is impossibly large beyond that hallway–like, we’re talking miles and miles in every direction–and dangers lurk within.

This is all related to us secondhand in the form of what appears to be a critical series of essays on the movie that those tapes were combined into. Those essays, titled The Navidson Record, are written by a fictional author, Zampanò. While we are given those essays directly (it’s how we learn most of what happens in the house, by Z’s discussion of the film and the public’s reaction to it), that’s only half the book. The other half, relayed to us in Courier font and with no shortage of expletives and unhealthy behavior, is the first-person account of Johnny Truant, an aimless underachiever who has discovered Zampanò’s book in manuscript form. Despite no one in his reality ever having heard of Navidson or his house, Johnny becomes obsessed with the story and starts to lose his grip on reality.

The second part of the novel’s complexity is the typography and formatting of the book. This in particular sets HoL apart from other novels. While some chapters are in straightforward paragraphs, others break wildly from convention. It’s not unusual to see multiple columns of text crisscrossing on a page; struck-out, removed, or different-colored text; or ample white space that makes concrete forms out of words. Upside-down text. Footnotes galore (which sometimes switch narrators in the process).

In one of the more convoluted chapters of the book, a square an inch or two wide on the right page is displayed on the backside of that page (the left side when you turn to the next page) like a window: the text on the front appears on the back, but the letters are backwards, giving a three-dimensionality to the words themselves. This chaos in form appropriately ramps up as the book goes on and Navidson and his team continue to explore the endless unknown of the house, amplifying the disorienting nature of their journey (and Johnny’s mindset).

And of course, I mentioned wordiness: the novel is pretty lengthy, coming in at around 700 pages, but it doesn’t stop there. The book’s latter ~150 pages are comprised of multiple appendices filled with correspondence, “evidence,” sketches, photos, poems, quotes, and additional context that changes, in a few cases, major aspects of the story the reader experiences.

There’s certainly a lot more to House of Leaves, but for today this summary will suffice to set the tone for our build. (Also, if it’s not clear to you from this whole article, I love this book and if it sounds even a little interesting to you I recommend you try it out! If reading a book with this much going on sounds less fun to you personally than a week-long dental appointment, I get it, this one might not be for you! But stick around for the deck at least!)

In honor of HoL and its celebration of layered, dark, and format-innovative storytelling, let’s build a Commander deck that sure, shows off some wordy cards, but also lets us warp the way the battlefield is shaped, making a labyrinth of not only words but mechanics for our opponents to try and get through.

Our ingredients? “Zone” mechanics, labyrinths, and darkness. Let’s peer into the depths (of Scryfall) and see what we can find.

Preparation

First, we’re going to need a general to helm this deck. There are very specific cards we want to run without replacements, so I think we need to use a five-color commander to make sure we have access to everything. Thematically, I think our best options among WUBRG legendaries are Progenitus, Garth One-Eye, and Karona, False God. Progenitus is a kind of ancient, impossible-to-overcome power that feels similar to the forces invoked within the book’s house. Karona is a force that can come at you unexpectedly from any angle, so there are some resonances there too. But I think our best choice is Garth.

Garth does a halfway decent impression of the study-of-a-fictional-film-within-a-book’s author Zampanò, but much more importantly he gives us more cards to read: six more, in fact! Being able to cast illusory (but totally real as far as the game state is concerned) old-school Magic cards both fits with the old card vibe a portion of our deck will have and the kind of information overload we’re flirting with.

Zone Mechanics

Garth is a pretty open-ended commander, so giving the deck a unique identity will need to happen in the 99. Tonally, there’s plenty for us to work with (see the next section below), but I want to see if we can mechanically represent the disorienting and rigidly structured elements of House of Leaves. The two cards that come to mind immediately are Raging River and Space Beleren.

Both cards ask players to place their creatures in arbitrary zones; sides of the river for the former and “sectors” for the latter. A pitch-black, endless, and shifting labyrinth is hard to get through for the novel’s characters (and maybe for some a 700-page novel is just as hard), and by dividing up the battlefield in these ways, especially if both are on board at once, we can make traversing combat difficult for our opponents’ attacking creatures (in the case of River) or blockers (when it comes to Space Jace, who also threatens a 1/3 board wipe at any time).

These cards and some other staples to protect us will be the foundation of how this deck works, so we’ll run a handful of tutors, like Enlightened Tutor and Call the Gatewatch, to consistently set them up in our games.

Labyrinths and Darkness

Our goal is to make it hard for opponents to proceed with their gameplan if that plan involves attacking with creatures. Zone cards make it harder, but not impossible, so we need to throw more in their way. There are handful of lands that make creatures lose their way mid-combat; fittingly, those are all represented as mazes or labyrinths. We can use them with little cost to our deckbuilding, since they just take up a land slot and will cast our spells when we don’t need to keep them at the ready. The exception here, of course, is the original Maze of Ith, which doesn’t tap for mana, but a manaless activation is way too good to pass up. (Besides, that’s what Urborg, Tomb of Yawgmoth is for!)

It’s going to be hard for our adversaries to navigate the convoluted system we build on the battlefield and get to us for damage. On the offensive side, a number of our creatures are appropriately hiding in the darkness, since they have (or can gain) shadow. That effectively makes them unblockable against 99.9% of the battlefield, allowing us to start chipping away at life totals while our opponents are lost in our maze.

Add in Stand or Fall, an offensive Zone mechanic that will aid those of our creatures without Shadow, and blocking is going to be difficult for them, too, especially when we’re combining some of these zone effects to make choosing the proper blocking sequence complex and perhaps impossible.

The darkness is our friend in this deck, and if a creature does manage to get through our maze of battlefield configurations, Wall of Shadows can soak up a non-trampling attacker, and we have a one-time panic button in plain ol’ Darkness.

Wordy Spells

And of course, we’ll keep those couple super wordy spells. Camouflage fits in perfectly with our gameplan, as it makes, in so many words, blocks random for a turn. Illusionary Mask disguises our creatures (within their mana value) and, while we have to flip them up when they attack or do anything else meaningful, it’s still less information for our opponents to go off of.

Word of Command is…well, it’s expensive, don’t buy it for this deck, but for the purpose of our hypothetical deckbuilding it’s about as dark as it gets: you possess your opponent for as long as it takes to make them cast something they don’t want to from their hand. Make them board wipe when they’re ahead on board! Have them spend their turn Beast Within-ing their own The Great Henge! Fun!

We’ll also add a couple more wordy cards that fit into our gameplan. Tawnos’s Coffin gives us insurance (both removing a problematic creature that isn’t even interested in combat) or protecting our own stuff. Arcum’s Whistle, a card I did not know existed before today, will force our opponents to figure out a way through their maze or else lose their best creature.

And, well, it’s not just wordy spells we want…we can use wordy lands! Even the basics, thanks to that Secret Lair that made basic lands full-text and no art.

How does the deck win?

The basic gameplan is clear: we can attack profitably since our shadow creatures don’t really care about zones or blocking configurations, and our opponents won’t be able to retaliate against us effectively due to the many roadblocks we put in their way. Moraug, Fury of Akoum is our beast hiding in the depths of the house (IYKYK) and will let us get extra combat steps to take out our opponents.

There are also a couple additional planeswalkers that can more or less win the game if left unchecked in the form of Tevesh Szat, Doom of Fools and Chandra, Awakened Inferno; if our shadowy pillowfort is set up properly, a few turns of these doing their thing and we’ll be golden. We’re also packing a few haymakers in the form of Insurrection and Rise of the Dark Realms if the game goes long.

Speaking of pillowforts, there is a downside to the pseudo-unblockable of shadow, which is that many of our creatures won’t be able to block practically anything unless they lose shadow, so we’ll use cards like No Mercy and Ghostly Prison (that’s one way to think about Navidson’s house, that’s for sure) to dissuade opposing creatures from even wanting to venture into our confusing battlefield. No Mercy also has the nice upside of taking out the various Guttersnipes of the world, since it’s any damage that sets it off, not just combat damage.

Yield

Here’s our long-winded contraption!

That’s it for this iteration of Flavor of the Month! If you’re a fan of House of Leaves already, I’d love to hear your thoughts; even better, if you weren’t a fan before (or hadn’t heard of it), but now want to check it out, that’s the best scenario I can think of.

Join us next time when we… well, that’s as of yet undecided! I always have a long list of ideas for articles, but I’d love to hear from readers if there are any flavor- or flavor-text-focused builds you’d like to see done.

Until next time, thanks for reading!